[This column appears in the July/August 2021 issue of Boston Spirit magazine. Subscribe for free today.]

“There was no word for it, no language, no history, no information, no support systems and no role models.” This is how David Weekley, 70, from Hull, describes the era in which he transitioned from female to male.

The ’70s was a turbulent time in this country characterized by protests, economic upheavals the war in Vietnam. Certainly not a time to explore a gender reassignment when the procedure was unheard of. One might imagine that someone struggling with their identity at this time would face a lonely path without any support systems. But that is not David’s story.

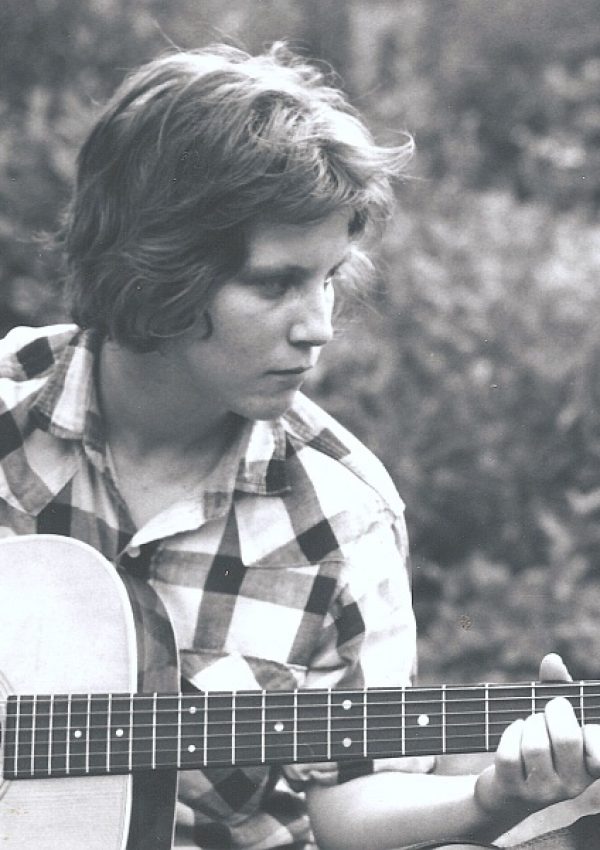

A question that is often asked of LGBT people is “When did you know you were different?” David’s answer was unique: “There was nothing wrong with me; I noticed that others felt my behavior was different.” Everything fell into place one day when he was 12 and starting a band in a friend’s garage. He heard his friend’s mother talking about news that an American GI went to Denmark to receive surgery to become a woman, Christine Jorgenson. Even as a child, from that moment, David knew what he had to do—start getting odd jobs and save money to get to Denmark and get that surgery.

That is exactly the path he began to follow. He started mowing lawns, shoveling in winter, even caring for a neighbor’s horse, but David still needed to graduate from high school. School was a cruel time, and often some of the worst cruelty came from his teachers. He was frequently expelled from school for wearing boys clothes and violating the gender-specific dress code of the ’60s. But he finally confided in his 10th grade English teacher in high school, and she was incredibly supportive and she spoke to the school psychologist. These two people became David’s first support system. The psychologist met with him regularly and encouraged David to tell his parents. At that point he had told a few close friends and used them to practice telling his parents. When he did tell his parents and older brother, they were all supportive but had no idea how to guide him through this process. The psychologist began to do some research to find out if anyone in America was starting to look at this kind of surgery. And to their surprise there was a brand-new clinic made of a consortium from Cleveland Metropolitan Hospital, The Cleveland Clinic and the Cleveland University Hospital just minutes from the town where David and his family lived.

The staff at this clinic met with David and his parents, but they had very strict protocols that prohibited any medical interventions until David was 21. The next step was for David to meet individually with each member of the team that included a psychologist, a psychiatrist, a urologist, a plastic surgeon, a social worker and an anesthesiologist. All six had to consent before he could move forward. It is important to note here that at this time in the early ’70s there was only one way to transition—a complete sex reassignment surgery, which is now called a gender affirmation surgery. Today, many people who identify as transgender have never had any surgeries and there are some who do not take hormones. There was a lot of apprehension, especially from the urologist because this would be his first phalloplasty surgery, with the removal of the vagina and creation of a penis through skin grafts.

As David got closer to the age he could undergo the procedures, he was told that another requirement was for him to live a full year in his identified gender, and required getting a job in that gender. He was able to land a security job that didn’t check his records.

There were so many details, beyond the basic medical procedures in this transformation to becoming his authentic self. One of those details was the new name he would choose. Again, there were no role models or guidance to go about this. David began checking out books from the library on baby names, which probably further confused his parents! Spirituality has always been a foundational point in his life, so he settled on David, which means “beloved of God,” and Elias as his middle name, which means “servant of God.” There was no question about his last name; it was Weekley, the name he was born with.

At 25, David underwent the phalloplasty surgery. He spent a full month in the hospital and ended up missing an entire semester of school because of the painful recovery. But the following year when all the procedures were complete, he describes the feeling of finally being his authentic self and feeling the sun on his chest. “I felt great about my body and myself, I loved the feeling of the sun on my chest. I was finally able to express myself the way I always wanted. It was indescribable.”

At that time the general guidance for the first Americans undergoing sex reassignment surgeries was to completely drop out of their former life and move far away to a different city as a new person, leaving family and loved ones behind without looking back. The other wisdom of the day was to tell no one about your identity unless it was an emergency. David did move across Ohio to start grad school, but family was so important to him that he traveled home every chance he could get. He even worked with his brother who was a long-haul trucker, and he remembers being touched when his brother introduced him to all his trucker friends as “my brother David.” Another special family moment was when his grandfather taught him to tie a necktie before his first job interview. It is simply amazing to recognize all the support David had during a time in our history when there was no mention anywhere of transgender people.

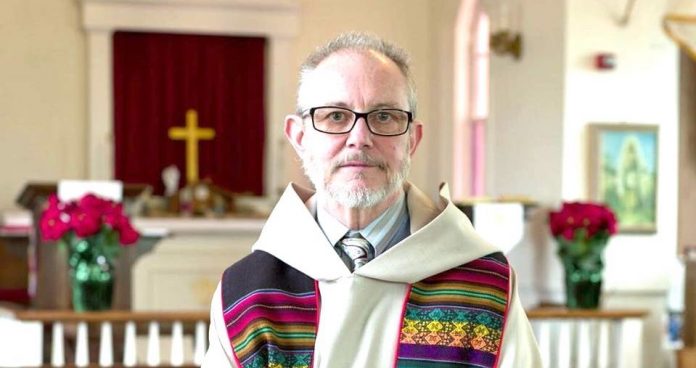

Not too long after his transition, David, who was drawn more deeply now to a spiritual path went into seminary and was ordained as pastor in the United Methodist Church. He moved to Oregon to be the pastor for a Japanese-American community in Portland. Since the Methodist Church had a terrible reputation around intolerance for gay and lesbian issues, he did not reveal that he was transgender.

During his time in Portland as a pastor, he was asked to help the community with a “gang problem.” Everyone on the task force wanted to pursue strict punitive measures except for David and one of the women on the committee. They wanted to build a skate park, and they did. And David fell in love and married that woman.

After three years with his Parish, he felt he needed to tell the congregation his story. This would be a big deal and he could risk everything. The church leadership, who was not supportive of this at all, insisted that he would need to make a formal announcement with a question-and-answer session with his congregation. If that didn’t go well, he would have to leave. The night before this big event, his wife asked him if he was sure he wanted to do this. “Our lives will never be the same again,” she said. But David trusted his faith, and the following morning when they headed to the parish hall for this intense meeting, they opened the doors to find it fully decorated with tables of food. The parishioners had somehow figured everything out and decided to hold a celebration for David conveying their acceptance.

Now at 70, David has been with his wife for nearly 30 years and is a pastor at St Nicholas United Methodist Church in Hull. Ever since that early placement in Oregon, he has been fully out in every aspect of his life. He has dedicated much of his time to developing retreats to support other transgender people, especially ones committed to a spiritual path. He has written two books about his experiences, “In from the Wilderness” and “Retreating Forward.” He was also profiled in the groundbreaking book “To Survive on This Shore: Photographs and Interviews with Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Older Adults,” by Vanessa Fabbre and Jess T. Dugan.

David’s story is unique, it highlights someone who sought to find their authentic self at a time when there was no language for this and he found support through his family, medical providers and the church. Those are three areas that have caused considerable pain in many transgender Americans.

The next Senior Spirit column will feature a different story of a Boston woman who transitioned just a few years ago at age 60, which will illuminate the progress and opportunities provided to people in this century who are on a similar journey to live their true life.

Bob Linscott is assistant director of the LGBT Aging Project at The Fenway Institute

Not a subscriber? Sign up today for a free subscription to Boston Spirit magazine, New England’s premier LGBT magazine. We will send you a copy of Boston Spirit 6 times per year and we never sell/rent our subscriber information. Click HERE to sign up!