[This article appears in the January/February 2021 issue of Boston Spirit magazine.]

In James Baldwin’s “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” the protagonist, thinly veiled as himself, wrestles with two critical questions: What does it mean to be a Black American, and what does it mean to be gay? One answer is located in the Black church. For Baldwin, the church functions as a site of worship and as a site of sexual awakening. For many Black LGBTQs, in the Black church, the nexus is in gospel music.

There is an undeniable queerness to gospel music, a particular interpretation and expressiveness by LGBTQs- churched and unchurched. As repressive as the Black church is around openly LGBTQs, many of us nonetheless are drawn to its gospel music.

“It’s Black folks’ prayer and lamentation. It’s our language and expression as a people that cannot be taken away. It speaks to times of great joy and sorrow. It mirrors my breath and the beating of my heart. It is soul-stirring, and a meditation with your spirit with whoever and whatever is your God,” Gary Bailey waxed poetically. Bailey is professor of practice and assistant dean for community engagement and social justice at Simmons School of Social Work, and is a member of Union United Methodist Church, the first “open and affirming” Black church in New England.

The Black church applauds its LGBTQ congregants in the choir pews yet excoriate us from the pulpits. It pimps our talent yet damns our souls with the theological qualifier of “love the sinner but hate the sin.” Our connections and contributions to the larger Black religious cosmos are desecrated every time homophobic pronouncements go unchecked in these holy places of worship. However, our pull to gospel music is seen as a calling, a distinctive gift to the church, and an expression of queer pain and hardship.

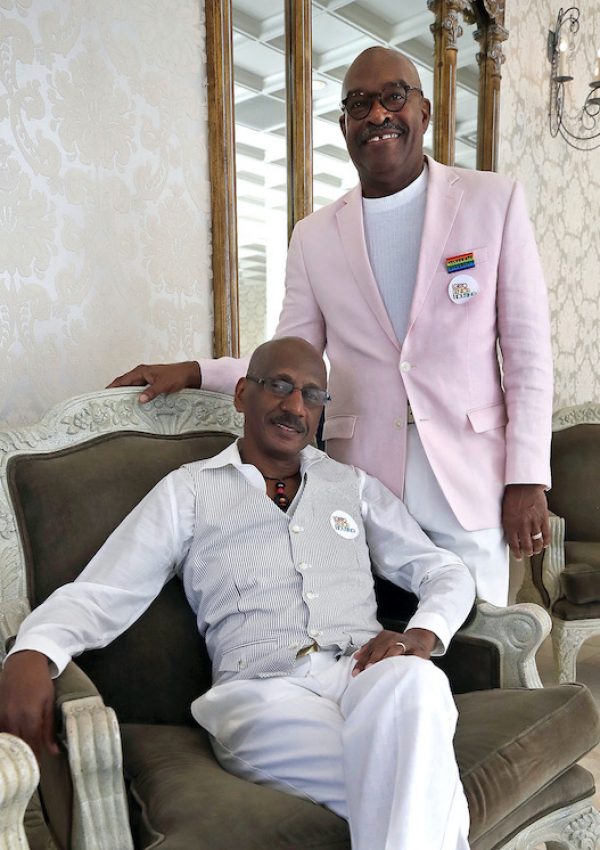

For Charles Evans, “Gospel music is tied to suffering, black suffering and certainly black gay suffering. It communicates our trials and tribulations through song that a better day will come.” Evans grew up in the Jim Crow South. As a college student in North Carolina, he sat at an all-white lunch counter as a form of nonviolent direct action protesting the store’s segregated seating policy. Both Evans, former vice president of Cape Cod Pride, and his spouse, Paul Glass, president of LGBT Elders of Color, are veterans of the 1969 Stonewall Rebellion.

A closeted queer denomination

Gospel music undeniably has queerness in its roots that shaped the genre and gives gospel music its enduring vibrancy. However, not all Black churches with gospel choirs are alike. There is “high church” like the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) and Methodist and “low church” like Baptist and Pentecostal, to name a few. I attended both Baptist and Pentecostal churches in my informative years, and I call myself “Bapticostal,” a telling portmanteau. Those churches’ worship was expressive and charismatic, with glossolalia, hand-clapping, dancing, prophecy, laying on of hands, and being “slain in the Spirit.”

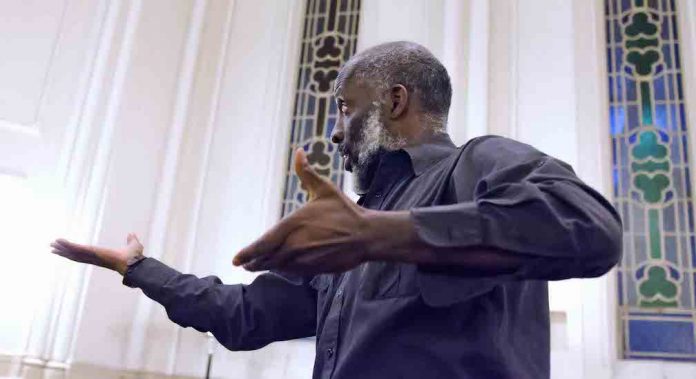

Donell Patterson told me his “entire life has been gospel music,” and he has the resume to prove it. Patterson is chair of the Gospel Music department in New England Conservatory’s School of Preparatory and Continuing Education and has conducted three renowned Gospel Choirs in the Boston Area. Patterson has observed through the years that some Black church denominations are queerer than others. “Those denominations are more open to gays without announcing it, because of its liturgy and organizational structure like Pentecostal churches,” Patterson shared.

The Church of God in Christ (COGIC) is the largest Black and Pentecostal church in the United States. Many of the gospel music industry mega-stars are from COGIC. The church, however, is conflicted with itself. These Black gay male mega-stars are always forced to go back into the closet, publicly denouncing their sexual orientation at the church’s annual convocation.

Case in point: Speaking at the COGIC’s 102nd Holy Convocation International Youth Department Worship Service in 2009, Pastor Donnie McClurkin is one of them. McClurkin is a three-time Gospel Grammy winner, was a revered judge on BET’s “Sunday Best,” a reality TV-gospel singing competition show, and the poster boy for African American ex-gay ministries.

At the 2009 convocation, McClurkin espoused his ex-gay rhetoric castigating former gospel industry worker Tonéx (B. Slade), who unapologetically stated that he “didn’t struggle with his sexual attraction to men.” As a talented singer, songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, rapper, dancer, producer and preacher, Tonéx has won six Stellar Awards, a Gospel Music Association Award, and received a Grammy nomination for Best Soul Gospel Album for his 2004 gold album, “Out the Box.” Known for his outlandish multicolored hairstyles and flamboyant garbs with feather boas, fur coats, Tonéx’s image caused consternation in the Black gospel and contemporary Christian music communities.

According to McClurkin, Black males, like Tonéx, are gay because of sexual molestation, an absentee father, or they didn’t have strong male images around them. McClurkin attributed his homosexuality to being raped twice as a child. Confusing, however, same-gender sexual violence with homosexuality, McClurkin misinterpreted the molestation as the reason for his gay sexual orientation. McClurkin’s testimony that a deliverance from God restored his manhood by becoming a child’s biological father is bogus. Tonéx, however, is the son of the revered late Dr. Anthony Williams, senior pastor and district elder in the Truth Apostolic Community Church in suburban Spring Valley, California. What makes Tonéx unique is not that he was once a gay gospel music artist and pastor, but rather he told the truth about his sexuality.

The Church of God in Christ was formed in 1897 by a group of disfellowshipped Baptists. The guys were booted out because they were gay. However, today, gay males, in particular, continue to find ways of being supported in the COGIC. For example, “blaquebigayministers” is a Yahoo gay ministers’ group, boasting over 787 members since July 2000. The “blaquebigayministers” website states the following:

“WELCOME. This fellowship is for support and encouragement, especially of black Christian ministers and friends who are ‘family’ (bi or same-gender-loving) and need a place of refuge. Enjoy the ‘fellowship.’”

A report following the 2009 Convocation asked, “Is COGIC going to be silent while an organized culture of homosexual ministers and bishops populate its pulpits?” COGIC cannot deny that the church gets its Jesus dance on and Amen shouts to a black gay male queer gospel aesthetic every Sunday, and no one knows it better than McClurkin himself. “A day without gay people in the choir, there would be no church and in some cases pastors, too. Gays are integral to the black church, and it can’t deny it,” Patterson stated emphatically.

Pastor McClurkin’s homophobic past came back to haunt him in 2010, however. McClurkin was billed as the main event in the 2010 Boston Gospelfest, and many African American LGBTQ communities were not in attendance that year. Neither was the mayor. Every year Mayor Tom Menino’s Office of Arts, Tourism and Special Events put on its annual Boston GospelFest at City Hall Plaza. The Gospelfest was a public and taxpayer-funded community event; therefore, it was open to all—even Black LGBTQ communities.

“I learned yesterday—through the ‘Phoenix’ article regarding the City of Boston Gospel Fest—of the depth and breadth of Donnie McClurkin’s views on the gay community,” Julie Burns wrote to me in an email. Burns was then the director of arts, tourism and special events for the Mayor’s Office.

“I am embarrassed to say that I was not aware of this, and we obviously should have vetted him further. Gospel Fest is in its 10th year and is arguably the largest gospel event in New England. Minister McClurkin was recommended to us by a number of people, and we were swayed by his artistic honors. Of course, this does not excuse the situation that we now find ourselves in! Please rest assured that Mayor Menino did not know anything about this and would never condone ‘hate speech’ of any kind.”

Menino had the trust and respect among both Black and LGBTQ communities. However, when it came to moving Boston’s black ministers on LGBTQ civil rights, Menino’s struggle had been and was like that of other elected officials and queer activists—immovable. His absence from that year’s Gospelfest was another example of how Boston’s black ministers—an influential and powerful political voting bloc of the mayor’s—would rather compromise their decades-long friendship with City Hall than denounce McClurkin’s appearance.

Black Masculinity

Toxic masculinity contributed to the early years of AIDS ravaging the gospel industry. The effects of AIDS were widely discussed but rarely publicly acknowledged until the death of James Cleveland, the King of Gospel, in 1991. Cleveland was influential in bringing gay men into the industry. He was a fixture at gay parties in cities he toured, and it was an open secret. However, the most devastating news following Cleveland’s death was when a male member of Cleveland’s choir sued his estate, alleging he contracted HIV during their five-year sexual relationship.

Homophobia and hypermasculinity are rebuked by many openly gay men in gospel music. They see it as a complex welcome space, allowing enough wiggle room to be themselves. “Gospel music allows you to emote where you can be openly expressive in public with your emotions that you can’t be with your sexuality. In gospel music, you don’t have to suppress either,” Glass states. “Women and gay men can allow the music to take them where heterosexual men cannot go.”

I agree with Glass. For me, gospel music is an embodied musical extravaganza. It reminds me that our bodies are our temples, housing the most sacred, and scariest truth about us: our sexuality. Through gospel music, I learned that sexuality is an essential part of being human. It is an expression of who we are; it is a language, and a means to communicate our spiritual need for intimate communion-human and divine. When we embrace the Christian mind-body dualism, we lose our bodies, sexualities and spirit. Gospel music helps me not to forget that our sexuality is a spiritual site of revelation, an intimation of the holy unavailable in any other experience, and a source of our capacity for transcendence.

However, that ability to experience an embodied spirituality is truncated by the church, school and homophobic peers.

For example, in 2019, I went to see Tarell Alvin McCraney’s “Choir Boy” at Boston’s SpeakEasy. McCraney’s 2016 Oscar-winning screenplay “Moonlight,” he co-wrote with Barry Jenkins. “Choir Boy” is a “coming-of-age” narrative set at the elite all-Black prep school for boys in the 1980s. McCraney adeptly brings his audience into young Black boys’ interior lives wrestling with their dreams, parental and societal expectations, and sexuality and sexual identities. The play highlights the intersectional realities of being Black, gay and spiritual through the protagonist Pharus Young. Young is an academically bright and musically gifted gay male scholarship student who leads the school choir. Young embraces his sexuality unapologetically. Pharus’s antagonist, however, a legacy admission student, gay-bashes Pharus every chance he could. The tension between the two young males illustrates how homophobia mangles and maims at such tender and formative years. The possibility for a healthy Black masculinity that is inclusive of a brotherhood embracing different sexual orientations and gender identities is never broached in the play, mirroring, for the most part, where much of the Black community still stands on this issue in 2021.

In the 1980s—the same era “Choir Boy” is set—Morehouse, the jewel of black academia and male leadership, was a dangerous campus for openly GBTQ. It was then listed on the Princeton Review’s top 20 homophobic schools. However, in 2020, Morehouse admitted transgender male students to its incoming class, and there’s talk of creating an openly gay gospel choir.

Our gift to the church

Gospel music is theater and dramatics rolled up in song. With its overtly gay overtones, Gospel music is in the DNA of both Black sacred and secular cultures. It cannot be overlooked in its influence in Aretha’s songs, Little Richard’s flamboyant performances, Alvin Ailey’s signature dance piece “Revelations” or the public fire and brimstone exhortations of James Baldwin whether at the pulpit or in his writings. “You can’t listen to them and not hear the gospel influence or hear the music of the church in them,” Bailey stated. “And, as for Black gay men, well, it allows us to be peacocks with our multicolored feathers on display.”

Not a subscriber? Sign up today for a free subscription to Boston Spirit magazine, New England’s premier LGBT magazine. We will send you a copy of Boston Spirit 6 times per year and we never sell/rent our subscriber information. Click HERE to sign up!