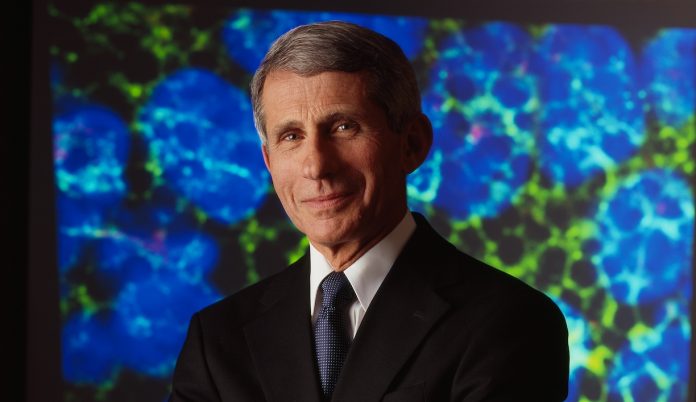

Most LGBTQA veterans of the AIDS epidemic, going back to early days, are familiar with Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and one of our leading scientists responding to the current COVID-19 crisis. And increasingly so is just about everyone else in America, at least over the past weeks.

As a recent article in TheBodyPro online newsletter for the HIV/AIDS workforce put it:

“The straight-talking, down-to-earth, Brooklyn-accented 79-year-old Fauci, who has held his post through six presidential administrations and more than a few epidemics (including AIDS, SARS, Ebola, and Zika) dating back to Reagan, [has] suddenly [become] a much-trusted household name.”

In this important article, contributing editor Tim Murphy recounts Fauci’s “long and complex history” (you can read the entire piece by clicking here)—which explains why Fauci has long been a proven ally to LGBTQ people and is still very much a highly competent expert for our current challenges:

[His recent media attention has been] all a bit amusing to watch for the handful of veteran AIDS activists who have a long history with Fauci, one that went from frustrated and adversarial to friendly and collaborative in the space of only a few short years in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

In that time, Fauci, simultaneously sitting down amiably with some ACT UP activists while parrying more belligerent public protests from their comrades, opened himself up to activist recommendations. Most notably, he dramatically loosened HIV-drug clinical trial requirements so that a far greater number of desperate patients could try new compounds (an approach called “parallel tracking”), expanded research on HIV/AIDS and its treatment in underrepresented women and/or people of color, and gave activists and people living with HIV seats at the table of the planning committee of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG).

Fauci also played a key role in getting the federal research apparatus to incorporate those recommendations, in what amounted to perhaps the first time that federal health bureaucrats acceded almost fully to community and activist demands.

“He’s the man for this moment,” says Peter Staley, an ACT UP and Treatment Action Group (TAG) veteran who grew so close to Fauci that they would often have dinner together at the Washington, D.C., home of Fauci’s assistant, James Hill, Ph.D. “He’s always had skills that are matched for epidemics. He’s one of the best scientists on epidemic control, but he can translate the complexities of epidemics into lay terms in a way that engenders trust to almost any audience he speaks to.”

Says Jim Eigo, also an ACT UP treatment activist veteran, “Fauci was a sparring partner with us, and then a friend.” He recalls the letter of recommendation for parallel tracking that he and other ACT UPers sent to Fauci.

“Lo and behold,” says Eigo, “he read the letter and liked it, and the following year he started promoting the idea of a parallel track for AIDS drugs to the FDA. Had he not helped us push that through, we couldn’t have gotten a lot of the cousin drugs to AZT, such as ddC and ddI, approved so fast. They were problematic drugs”—they would prove to have serious side effects—“but without them, we couldn’t have kept so many people alive,” he says. Those drugs held the line until protease inhibitors and NNRTIs emerged in the mid-to-late 1990s to form a truly effective treatment combination.

Also, adds Eigo, “Fauci, despite being straight and Catholic, was not only not homophobic, which much of medical practice still was in the late 1980s, he also wouldn’t tolerate homophobia among his colleagues. He knew there was no place for that in a public-health crisis.”

However, some ACT UP veterans have less rapturous memories of Fauci. “I would say that at the beginning of his encounters with us, he was a pretty typical bureaucrat, making excuses for the slow pace of drug investigations and approval,” says Ann Northrop, adding, “I still give him credit for turning into someone who listened more to the activist point of view and eventually became more of an ally.”

Maxine Wolfe, who worked primarily on ACT UP’s women’s committee, is not as measured. She recalls activists pressuring the National Institutes of Health (NIH, of which NIAID is a part) to hold a women and AIDS conference in 1990. “They wanted it to be all government people, and we set it up so it wasn’t,” she recalls. “The audience was mostly women, many living with HIV, and those who worked with women. Fauci gets up on a stage and says to about 1,600 of us, ‘I really don’t know anything about women and AIDS, but I’m going to talk to you about the virus and how it operates.’ And one of the women living with HIV grabbed the mic that had been set up in the audience for questions and said, ‘I don’t have a degree in anything but street-logy, but I don’t need an AIDS 101. I need to know what you’re going to do about women and AIDS.’ …

Fauci and Coronavirus: What Happens Now?

Regardless of what Fauci did or didn’t do at the height of the U.S. HIV/AIDS crisis, the question now is: What role will he continue to play against COVID-19?

Despite his recent absence from press conferences, “I’ll bet he’s still working those 19-hour days,” says longtime HIV doc Howard Grossman, M.D., a former head of the American Academy of HIV Medicine. (Fauci is a well-known workaholic.) “We need him doing that a lot more than we need him in front of a camera making Trump look good.

“He’s an honorable and very smart man dealing with a lunatic president and trying to get good information out there,” Grossman continued. “He’s survived so many bad leaders but always managed to move the scientific agenda forward. You don’t stay in that job without figuring out how to keep on doing your work in the face of the worst kind of Republican governments.”

To put Grossman’s remark in context, it’s worth remembering that Ronald Reagan did not so much as offer a public comment on AIDS until 1987, six years into the epidemic; that Bill Clinton’s administration welshed on its promise to federally fund needle exchange; and that George W. Bush, although significantly advancing the fight against global AIDS, tasked anti-HIV efforts to Christian evangelicals who silenced both LGBT and harm-reduction voices in the U.S. and abroad.

Staley, as well, applauds the fine line currently being walked by Fauci, who himself in early March told Politico, “You don’t want to go to war with a president, but you got to walk the fine balance of making sure you continue to tell the truth.”

“He needs to stay in his scientific lane, because the political lane will gobble him up and spit him out,” says Staley. “His job is to keep himself in the room [with the presidential COVID-19 response team] and maintain Trump and Pence’s trust. He is not a member of the Resistance, and for us to want him to have a Resistance moment against Trump so we can pump our fists in the air, while countless lives are on the line, is just selfish and self-indulgent.”

Read the entire article by clicking here.

Not a subscriber? Sign up today for a free subscription to Boston Spirit magazine, New England’s premier LGBT magazine. We will send you a copy of Boston Spirit 6 times per year and we never sell/rent our subscriber information. Click HERE to sign up!