For nearly 35 years, he’s been helping New England LGBTs get the healthcare they deserve

By Mark Krone

Go ahead, try to shock Jerry Feuer, Fenway Health center’s longest serving clinician. Tell him about last night’s colorful sexual exploits that landed you in his office or stump him with a set of contradictory symptoms that even WebMD cannot decipher. What will you get? A few questions and no judgment, just a warm, steady professionalism you don’t see very often in a doctor’s office, especially if you are a LGBT person.

The diagnosis will likely be right on the money, too. Dr. Stephen Boswell, president and CEO of the Fenway, recalled recently, “Jerry saw a patient, a student from China, who had a fever with a very unusual pattern and Jerry took blood from him and made the diagnosis of malaria on the spot. I told him that I doubted any of the residents I worked with at Massachusetts General Hospital could have made the diagnosis any more rapidly.”

Gone is the bushy mustache and curly hair Feuer brought with him to the Fenway in October 1980 (he had volunteered there previously in the late ’70s). His hair may be a little thinner, but his eyes have lost none of their precise, calm focus. (Full disclosure, I’ve been a patient of Jerry’s since 1985.)

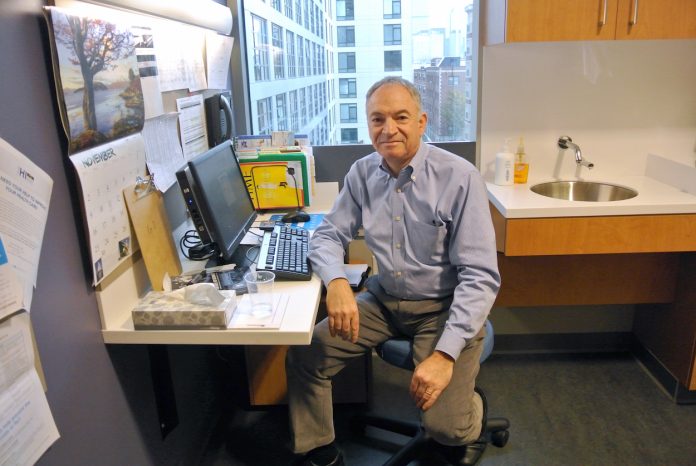

It’s 8:30 on a rainy morning and Feuer, 66, sits in his office, wearing a crisp button-down shirt and corduroys. He is ready to take on all comers, from lesbians interested in alternative insemination, gay teenagers worried they might have a STD, to long-term patients living with HIV. He answers questions, counsels and reassures. He is so calm and methodical, it’s hard to picture him raising his voice. Dr. Ken Mayer, research director of the Fenway Institute, who has known Feuer for over 30 years, has never seen it happen. “I’ve never seen him get into an argument with anyone or not get along with someone. With Jerry, there’s no drama. ”

But Feuer can be tough when needed, as a recent patient found out. He’d missed more appointments than he kept and wasn’t addressing long-term, pressing health problems. Finally, when he did show up, Feuer told him, “You have a choice to make. Do you want to live or not?”

Although he is never sure what will greet him when he enters an examination room, these days, there is a rhythm and routine to his day that was absent during the tumultuous ’80s and early ’90s. Just six months into Feuer’s tenure at the Fenway, in June, 1981, the Center for Disease Control’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report announced five cases of pneumocystis carinii pneumonia among previously healthy young men in Los Angeles. All of the men were described as homosexuals. Of the five, two were already dead.

Terrified and confused, young men began streaming into the Fenway, then at 16 Haviland Street, a basement warren. They sat on satin movie seats worn smooth from moviegoers and other worried patients. The seats had been rescued from the closed Fenway Theater. Feuer recalls, “In the beginning of the AIDS crisis, all we could do was help them cope with anxiety and sleep issues.”

During this time, the entire Fenway staff met weekly to support each other and grieve. “There was a book with names of patients who had died. If you hadn’t seen someone in a while, you’d check the book.” As bad as it was, Feuer didn’t bring the job home with him. “I am pretty good at compartmentalizing. I had two little ones at home and it was great to see life” after having dealt with death all day. But it was Feuer’s wife of 42 years, Alex, who ultimately kept him together. “It was due to her love and devotion that I was able to be available to my patients. She was the chief caregiver to our daughters.”

Founded in 1971 by a group of Northeastern University graduate students, nurses and community activists who believed that medical care was a right and not a commodity, the Fenway has become a world leader in LGBT health research and a model of compassionate care. In his book, For People, Not For Profit: A History of Fenway Health’s First Forty Years, Thomas Martorelli states that contrary to popular belief, the Fenway was not begun as a gay and lesbian health clinic. It was a community health center that served elderly Fenway residents, lesbians, gay men, students and anyone else who walked in the door. Like some gay bars, the Fenway acquired a reputation as a gay clinic in large part because it did not turn them away. It also didn’t hurt that there were regularly scheduled drop-in nights for women (many were lesbians) and gay men for education and treatment by volunteer medical practitioners.

When Feuer began at the Fenway, the board had just decided to move away from the collective, volunteer model on which it was founded in favor of a professional, licensed staff. This allowed it to receive Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements and ended threats by city and state officials who took a dim view of volunteers offering medical advice. The decision caused dissension among the board and some volunteers quit. But 35 years later, few doubt the decision.

At the Fenway, you have to remind people that Feuer is a straight man, with a wife and two grown daughters. It’s not that they don’t know, it’s that it doesn’t matter. “I think Jerry is in solidarity with underserved people,” says Dr. Boswell. “He has a strong sense of right and wrong.” Adds Dr. Mayer, “He knew he was very much needed during the early stages of the epidemic. He felt responsible to be there for his patients.”

A look at his past reveals a life rooted in social justice. Feuer lived in public housing in the Bronx until he was nine years old. In 1957, his father moved the family to Spring Valley, 22 miles north of New York City, opening a store in nearby Nyack. He graduated from the State University of New York at Cortland in 1970. He recalls, “I didn’t have a graduation because of Kent State, which happened on May 4, 1970.” National Guard troops had fired on a crowd of anti-war protesters on the campus of Kent State University in Ohio, killing four and wounding nine. As a result, Feuer says, “We all went home. The idea was to ‘bring the war home,’ meaning bring the protests to your local communities.”

“I met a woman who was graduating from Cornell and we got into a relationship. We moved into a big collective house in Ithaca, New York, with about 15 people.” The house included community organizers, academics and a few stoners. “I did some organizing against the Vietnam War.” On the first floor was a couple whose interests leaned toward music. They would go on to found Rounder Records, signing artists like Tom Paxton and Aaron Neville. When the Black Panther Party sent Huey Newton to Cornell to speak, he stayed the night in the house with guards surrounding it. “Things were always happening at that house.”

In 1972, Feuer moved to another collective, this time the Bowdoin Street Collective in Dorchester. He did organizing work for Fair Share, an organization working for economic and social justice. The times were exciting but Feuer needed to decide what he would do with the rest of his life. “I sat down and made a list of my attributes.”

He chose medicine and got a job as an orderly at Boston City Hospital (now Boston Medical Center). “I wasn’t the typical orderly, I asked questions of the residents and interns and they took an interest in me.” Feuer watched as residents interviewed patients and made diagnoses. In 1973, he enrolled in the physician assistant program at Northeastern University, graduating two years later. One of Feuer’s classmates at Northeastern, Ron Vachon, urged him to volunteer at a new health center in the Fenway. Feuer began seeing patients at the drop-in nights for gay men in 1978. “There was a piece of paper and people signed their names and we saw each of them in order, sometimes 60 in an evening … they’d put 50 cents in an envelope [to pay us].” He spent the summer of 1978 in Provincetown working at the Drop-In Center on Gosnold Street. Just three years out of school, Feuer already had extensive experience with gay patients.

In October 1980, Feuer was hired on an interim basis to fill a vacancy created when his classmate, Ron Vachon, left the Fenway. After a search, Feuer was hired permanently in January 1981 and he’s been at the Fenway ever since. No longer working in a tiny basement cubicle, Feuer says he has to pinch himself when he enters the gleaming Ansin Building on Boylston Street.

“They say things never change [if you stay in one place] but that’s not true here. Fenway has always been on the cutting edge, it’s always changing. And we’ve always had great leadership.”

After treating tens of thousands of people over the years during one of the worst epidemics in human history, does Feuer consider himself a hero?

“I don’t see myself as a hero, I see myself as doing my job.” Not a hero? His patients might offer a second opinion. [x]