Club Café celebrates 30 years as the heart of Boston’s gay scene

Club Café founder Frank Ribaudo will never forget his anniversary. Either of them.

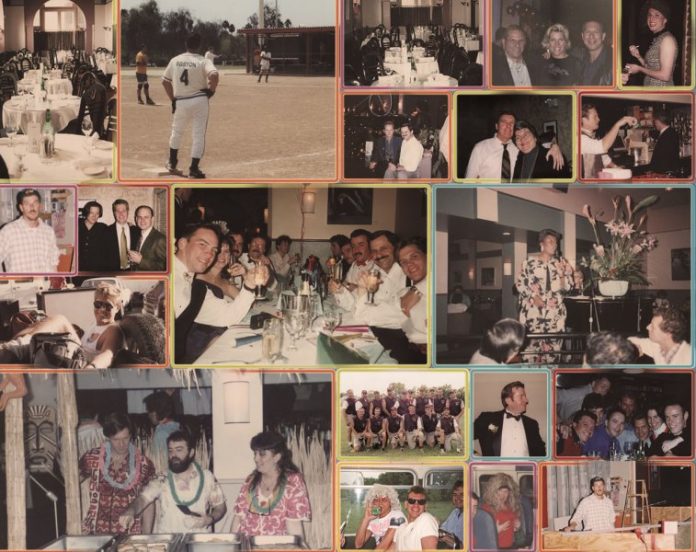

On October 13, Ribaudo will marry his longtime partner Joe Posa. They’ll celebrate their reception, which after certain hours will be open to the whole community, at Club Café. That’s because their wedding coincides with a second reason to celebrate. October marks the 30th anniversary of Club Café, which has become iconic in New England’s gay scene. For one generation, it has been a community center: a comfortable second home filled with old friends. For another, it’s a party palace: where stepping inside, grabbing your first drink, and scoring your first date has become a veritable rite of passage. And Club Café shows no sign of slowing down.

“2013 has been a banner year for us,” says Ribaudo joyfully. In a more accepting world, where it’s harder and harder to keep gay establishments afloat, Club Café is enjoying some of its best business.

But that success wasn’t always a sure thing, and Ribaudo admits that early on he never would have believed that Club Café could wind up a decades-spanning landmark in New England’s LGBT culture. “To be honest, for the first five years all I thought about was how to keep from going bankrupt,” says Ribaudo. “I don’t think we made a dime.”

That’s because 30 years ago, everything about Club Café was a calculated risk: from its willingness to challenge a bullying nearby business to its wide wall of windows that, in a brazen move at the time, planted a highly visible gay establishment right on the Boston streetscape.

Here’s the story of how it stayed there.

Building Its Muscle

The story of Club Café actually starts elsewhere: at Café Calypso, a gay South End restaurant founded over 30 years ago by Franco Campanello and his partner Caleb Davis.

“It was like a big frat house,” recalls Campanello of the early ‘80s South End, Boston’s gay ghetto. “You had all these twenty-somethings acting like college kids. For the first time they were free and easy. It was a wild place.”

“ For the first five years all I thought about was how to keep from going bankrupt. I don’t think we made a dime. ”

Frank Ribaudo, Owner, Club Café

Of course, the then-low income neighborhood was also kept like a frat house, a far cry from today’s post-gentrification landscape of fabulous restaurants and tony condos. Café Calypso shared space on Tremont Street, where it occupied the space that now belongs to upscale Indian restaurant Mela, with boarded up businesses and rat-infested tenements. “Neighbors would shoot BB guns through our window,” says Campanello. That wasn’t gay bashing, he clarifies, just a standard sign o’ the South End times.

Café Calypso helped spur the area’s redevelopment as a gay restaurant Mecca. “I like to think we showed that businesses could do well there,” says Campanello. “We broke the ice.” And so did Boston’s early gay leaders and activists, who gathered at Café Calypso to hammer out political moves and launch organizations over weekly breakfast meetings. There was one especially important person who walked through the door, says Campanello: developer Frank Ribaudo.

“I loved him because he was a mover and shaker who knew how to get things done,” says Campanello. Soon Ribaudo had invested in Café Calypso. Then the group tapped a fourth partner, Joe McAllister, for a risky new idea: a gay-focused gym, to be named Metropolitan Health Club, over at 209 Columbus Avenue.

It was a response to anti-gay discrimination at Back Bay Racquet Club, a block away in the space that now houses Da Vinci Ristorante, where gay clientele were harassed, intimidated, and threatened with physical harm. “If they thought someone was gay or seemed effeminate, they’d pull them into the office and push them around,” says Ribaudo. “They’d say, ‘We’ll break your legs if you come back here.’”

Ribaudo and his partners saw both a business opportunity and a chance for the gay community to fight back. But securing money was tough. Campanello says banks balked at loaning money to start a health club. “They were considered kind of sleazy,” says Campanello. “Not something a respectable bank would invest in.” He says the spot’s landlord, on board with the plan since the beginning, used his leverage on their behalf. “He picked up the loan, took it down to Shawmut Bank and said, ‘Do this loan,’” says Campanello. “And they did.”

Of course, that wasn’t all of it. “We tapped all our credit cards, sold stock, and borrowed money everywhere we could borrow,” says Ribaudo. But it quickly became clear that Metropolitan Health Club and its adjacent Club Café, then a small, annexed afterthought, would be filling a vital void in the gay community. Metropolitan began by offering 90-day memberships for $90: turn in your member’s card from another gym, and you’d get an additional 30 days free. “We set up tables in the lobby and sold $100,000 worth of memberships before we even opened,” says Campanello.

Metropolitan Health Club opened in October 1983. In four months it took in 800 members from Back Bay Racquet Club alone. Nine months later that gym was out of business. An abused community had flexed its muscle.

“That was the power of the gay community,” says Ribaudo.

By the mid-’80s, the founders decided to split the business. Campanello and Davis continued to own Metropolitan Health Club (later Columbus Athletic Club) downstairs until 2006. Ribaudo and McAllister took over the upstairs Club Café, then a mere fraction of its current size: 1800 square feet, versus today’s sprawling 8000 square feet space.

“It was just a little wine and beer bar,” says Ribaudo, who soon realized the real money was in liquor sales. So he scrounged up $31,000 to buy a license, a then-astronomical amount. And then he began the first of several additions to the space. Soon Club Café had a dining room and a nightclub component; at one point, Ribaudo even leased out space to a small tanning salon.

There was one element, though, that especially stood out: Club Café’s wide wall of curved windows. They were revolutionary, offering public visibility during a time when other local gay establishments, like Buddy’s, Chaps and The Napoleon Club were windowless, often-subterranean spaces that kept the community cloistered.

The windows, says Ribaudo, symbolized a refusal to remain hidden. And the profound effect of this new kind of space, one that brought the community out of the shadows and into the light, was not lost on its clientele.

“This place was far ahead of its time,” says Jim Morgrage. He started working at Club Café as a cocktail waiter in 1996; today he’s general manager and co-owner. But he still remembers the impact when he first started stopping in as a guest in the ‘80s. “Club Café was so different. We take it for granted now, but back in the ‘80s you didn’t sit at a tablecloth in the window, eating dinner with your same-sex partner. There wasn’t a place where you bring your mom or dad and be surrounded by your community.”

And though Ribaudo admits those first few years were lean (it didn’t help that Club Café was tucked down a dead-end passage amid an Orange Line construction zone), the spot soon became exactly that: a bustling community space. It wasn’t just a place to get liquored up and let loose. It became known as a de facto destination for gay-related social events and non-profit fundraisers.

In Boston, it built a gay community. Which was a response, partly, to almost losing one.

Opening Its Arms

There is an entire generation that remembers where they were when they first heard the news. That someone, a friend or a lover, was sick. And that no one knew much, except this: it was bad.

“Me and Caleb had just come back from a trip back from Hawaii, the same trip where he told me his idea for the gym,” recalls Campanello. “We found out that our baker at Café Calypso was sick with this strange disease.”

“He died in February, 1983.”

During the 1980s, the AIDS epidemic ravaged the gay community in Boston, as it did everywhere else. “Some guys would come into the health club so emaciated, so sick,” recalls Campanello, who held AIDS “health circles” at Metropolitan on Sunday after-hours. “You’d see people in the peak of fitness and bloom of health. And then you’d see these scarecrows. Every week there was a different memorial service.” He says he knew at least one hundred men who died from the disease.

“My entire phone book was decimated,” says Ribaudo. Every day, it seemed, another friend was lost. “A whole host of people who worked here passed. Most of the people I socialized with were gone.” The disease would eventually claim Club Café co-founder Joe McAllister in 1993.

And it took from Ribaudo his own partner, Tim Reed. “He used to work here,” says Ribaudo. “He was diagnosed in 1985. He passed on July 15, 1986.” Reed died in Ribaudo’s arms, taking his last breath as he was carried from the bed to the bathroom.

The experience was devastating to Ribaudo. And the loss of so many loved ones left the community profoundly saddened and deeply afraid, armed with plenty of prejudice but little education about how the disease actually spread. “We had customers come in for dinner, and they would bring their own silverware,” says Ribaudo. “That’s how petrified people were.”

The epidemic offered something else, though: a chance to come together, stronger than before. “It sort of thrust us into the middle of the epidemic,” says Ribaudo. “It forced the question, ‘What do we do about it?’” The answer was to act: from hosting Monday night pasta dinners to give early AIDS sufferers physical nourishment and emotional comfort, to launching large-scale events ever since. In 2003, Ribaudo worked with Michael Tye, a prominent Boston businessman and the AIDS activist who helped found Community Servings, to create Harbor to the Bay. That Boston-to-Provincetown bicycling benefit has since raised over $3 million, and over the years, Club Café’s commitment to social service has broadened to host major fundraisers for nearly every gay-related organization and issue.

Sometimes, its existence alone has been enough to make a difference.

Changing Others’ Minds

Though it has remained a major issue, better education and new medications began to quell much anxiety and panic over AIDS in the ‘90s. That collective exhale, coupled with a booming economy, made life at Club Café a gay old time, indeed. “That was a really strong time for us,” says Ribaudo of the Clinton era. “Everybody was going out then!”

And they had a new reason. In the ‘90s Club Café began hosting cabaret shows in its nightclub space. From local productions to big names like Eartha Kitt, shows were regular sell-outs. And whether as performers or VIP guests, celebrities started to swing through more often: Joan Rivers, Barry Manilow, Lily Tomlin, Leonard Nimoy and Kathleen Turner are just a few of the stars who have popped in for a drink (or three) over the years.

But the cabaret shows offered something more important than stargazing. “The crowds for the cabaret shows were predominantly straight, and there was this wonderful blending of clientele,” says Ribaudo, who prominently marketed the cabaret through mainstream media outlets. So even before Will & Grace plopped a gay best friend in every American’s living room, Club Café was giving many local straight folks their first real glimpse at gay culture.

“Frank was so forward thinking,” says straight singer Carol O’Shaughnessy, a longtime fixture on the cabaret scene. She has been a regular performer at Club Café since the day doors opened, and she says she always invited her straight crowds so they could see the community up close and personal. “It’s considered a gay club, but Frank always wanted it to be a place where everyone felt welcome.”

Because once worlds collide, society shifts. “I remember once a man and woman came in with their two children,” says bar manager Tony McCormick, who started working at Club Café in 1990 and has seen how its inclusive atmosphere redefined relationships with the straight community. “They asked for a table for four. I said sure, I just want you to know that we have a large gay clientele.” He’ll never forget her quick retort.

“Oh, do you think my children will offend them?” the woman responded, not missing a beat. Of course not, McCormick replied.

“Well then,” she nodded. “We’d like a table.”

Staying True To Its Heart

Of course, there’s a downside to assimilation. Over the last fifteen years or so, cities around the country have seen their gay clubs shutter. As acceptance grows and new generations grow up without the specter of discrimination looming overhead, the need for a safe space — somewhere explicitly aimed at the gay community — becomes less important to many.

“Things slowed down at the turn of the century,” admits Ribaudo. “As we’ve become accepted as a community, gay people have felt comfortable going anywhere. We lost a lot of business to straight establishments that opened their arms and embraced the gay community. The South End became very gentrified. More straight people moved in, and all these new restaurants opened up that were very well blended.”

In fact, Morgrage admits that one Club Café misstep was to try and compete with those spots. In 2005 the dining room was renovated and re-branded with a distinct restaurant identity, 209, and given a more ambitious menu. The effort was short-lived, and the period was “probably our toughest time,” says Morgrage. “We spent too much time and energy going after the dining room. There are five thousand restaurants in Boston and it’s hard to compete.” So rather than belabor competing in a crowded culinary-driven marketplace, the spot refocused its attention on being a multipurpose venue. “We embraced who we are,” says Morgrage. “A lounge and nightclub where you can get live entertainment, a good meal, and a good value.”

Re-embracing that identity was accompanied by big, very expensive renovations. In 2010 the main dining room was partitioned with a gorgeous, soundproof glass wall to create the Napoleon Room, an intimate area devoted to nightly live entertainment: sing-along piano bars, jazz musicians and other performers with especial appeal to older crowds. The more expansive back room was outfitted with a new, state-of-the-art audiovisual system; as the Moonshine Dance Club, it breathed new life into Club Café’s younger partiers. The lounge connecting these spaces received a layout tweak and second bar, and the whole club began emphasizing nightly programming: like Monday’s “Drag Bingo,” Tuesday’s “Stump Trivia,” Wednesday’s “Karaoke Kween” and Sunday’s “Back 2 Basics Tea Dance.” This summer Club Café also launched “Lady Love” on Thursdays, a collaboration with Lesbiannightlife.com, as an option for Boston’s underserved women’s community.

Ribaudo believes that evolving with the times and offering something for everyone is the key to Club Café’s continued success. “We keep making these little changes to maintain interest and operate in the middle of the bell curve,” says Ribaudo. “We’ve never looked to be too extreme. If you are, you’ll be hot to a limited number of people for a short period of time.” If anything, Club Café has broadened its appeal. Between bachelorette parties seeking a grope-free zone to the ally friends of gay regulars, straight folks constitute nearly a third of weekend crowds, says Ribaudo.

Club Café has also managed to retain a large number of longtime staff. There are about 50 employees, says Ribaudo, and many have been with the place nearly as long as its younger customers have been alive.

“It’s like a family, and Frank is the dad,” laughs bartender Mary Squires, who has worked at Club Café for 19 years. “When it comes to life in Boston, Club Café is my first family,” agrees bartender Todd Askew, whose first day of work happened to be Club Café’s 10th anniversary party. He says the place has always had a unique way of inspiring camaraderie.

“We used to have a really fun staff shows to raise money for one cause or another,” says Askew. “I remember once stepping on stage wearing just a cowboy hat and boots. I sang a song to my penis while I held a guitar over it,” he laughs. “I found it very odd that the loudest applause came when I turned to leave the stage.”

Those warm memories and familiar faces represent the ensconced sense of history Club Café has, and explains why even when some guests move away, they never quite move on. “I may not see someone for a couple years,” says McCormick. “But whenever there’s a reason to pull together, in celebration or mourning, everyone comes to Club Café. It’s a home base for the gay community.”

And even in a more accepting world, it will remain so for many years to come.

“On a Friday or Saturday night, half the people partying inside Club Café weren’t even born when it opened,” laughs McCormick. Yet they still seek it out, immersing themselves in what is, at this point, a legitimate landmark for the region’s gay community. “They still have their struggles, which are as important to them as ours were to us. Club Café gives them comfort, courage, and provides a place to play.”

“Every school has a playground,” says McCormick.

Let the music play on. [x]