Author Amy Hoffman says her second novel, “Dot and Ralfie,” isn’t autobiographical. But while writing her gently comic tale of a longtime lesbian couple now in their late 60s, Hoffman realized there were few representations of LGBTQ people as they navigate the physical, emotional and social challenges of aging.

“I came out in the 1970s, and especially for people like me, a middle class, white college student, I had no contact whatsoever with the previous generation of lesbians,” says Hoffman who lives in Jamaica Plain with wife Roberta Stone. “Many of those women were in the closet; they were involved in institutions like the bars, which I didn’t go to; the age gap and experience gap was huge, and that was scary to me. I couldn’t imagine what my life would look like and, of course, all the stereotypes were frightening—you’ll be unhappy, alone, suicidal. Those kinds of images were the ones we had of lesbians. As I got older and had a life that was nothing like those stereotypes, I felt I wanted to share some other possibilities on paper.”

Not that Hoffman wrote “Dot and Ralfie” to make any kind of statement or to educate anyone; she wrote it simply because “I wanted to … I’ve always had a day job. I teach, edit; I don’t make a living from writing, which is true for most writers,” she says.

“At one point, I had some fantasy of passing my experience to a new generation, but every generation has their own issues and nobody needs that from me. … I just loved these characters and how they think of their lives and what we of my generation are looking to in the future without people in front of us to look to.”

“Dot and Ralfie,” out now from the University of Wisconsin Press, is Hoffman’s second novel after her Provincetown-set “The Off Season” in 2019. Her fiction followed three highly regarded memoirs: “Hospital Time,” “An Army of Ex-Lovers: My Life at the Gay Community News” and “Lies About My Family.”

“I think I’d gotten to the end of the trail of memoir that I was working on and wanted to write a novel. That process had been intimidating to me before,” says Hoffman. “But it was fun, like a game, a puzzle. It just required a different part of my imagination, and I love creating characters and hearing them talk and make their way in the world. It didn’t require the same level of soul searching that writing the memoirs did.

“I started with the characters. I had an image of this couple for many years who became Dot and Ralfie … they’d been with me a long time, so they aged in my mind. I started with the first chapter and the words, ‘There’s Ralfie,’ and the book unfurled from there.”

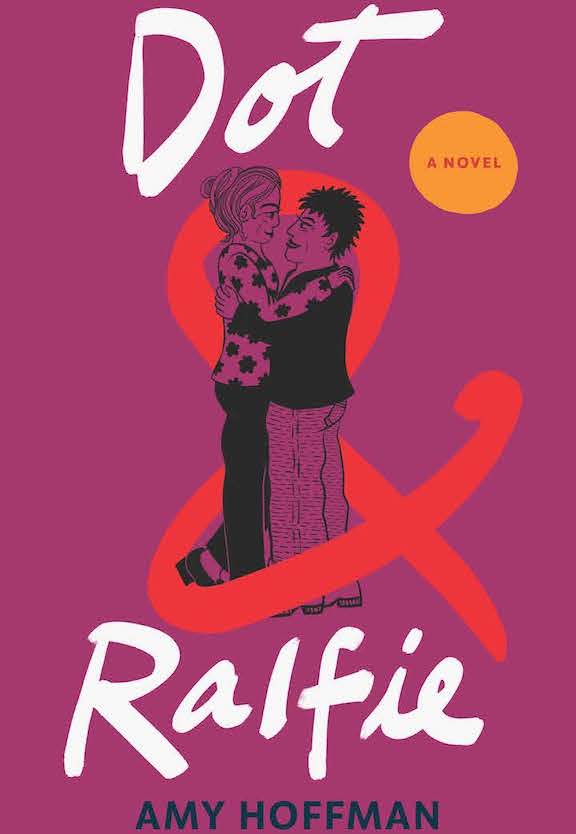

Acclaimed LGBTQ cartoonist Jennifer Camper’s cover illustration captures the playful, idiosyncratic spirit of the two characters. Hoffman wanted Camper to illustrate the cover; she’d admired Camper’s work since Camper drew cartoons for GCN and was comics editor for the Women’s Review of Books, which Hoffman edited for 14 years.

Even though raucous DPW worker Ralfie, who’s had knee replacement surgery, and librarian Dot, who’s dealing with a heart ailment, are not based on Hoffman specifically, she acknowledges the universal issues that face any long-term couple as the years unfold.

“I’ve been realizing personally that I am entering into a new phase of life and there are some scary things; seeing friends dealing with issues of disability, poverty, poor health care, all the things we are afraid of,” she says. “I think about that in my own life, and my characters are dealing with that. Dot reflects how when kids are small, little things like just tying a shoe are a big deal. As we get older, things also loom very large, like a set of stairs, which can ruin your life.”

Even though much of “Dot and Ralfie” is relatable to anyone, there are issues, such as isolation and ostracism in assisted living facilities, that are more complicated for LGBTQ people.

“How do we envision our lives as elders without a lot to go on? Some, like me, don’t have children. It doesn’t always work out that way, but the idea is your kids are supposed to take care of you. Also, I think with the usual issues of health care, housing and income, lesbians are in a particular place: there fewer opportunities; health care providers may not understand,” she says.

But as part of the LGBTQ community response to AIDS during the ’80s and’90s, Hoffman also learned the importance of creating community. “I lost quite a few friends. I was involved with taking care of people and I became an activist,” she says. “So on the other hand, we know what to do. I’m involved in care circles for friends with cancer or Alzheimer’s. We know how to do that. Community is the thread that runs through everything.”

Not a subscriber? Sign up today for a free subscription to Boston Spirit magazine, New England’s premier LGBT magazine. We will send you a copy of Boston Spirit 6 times per year and we never sell/rent our subscriber information. Click HERE to sign up!